Who Made Up The Grange, And What Effect Did They Have On The Writing Of The Texas Constitution?

Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was the 19th century U.S. belief that the country had a divine right to expand across and take over the continent.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate how the concept of manifest destiny shaped U.S. thought and movement

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The concept of manifest destiny, coined by a newspaper editor, justified American expansion across the continent.

- The phrase "manifest destiny" suggested that expansion across the American continent was obvious, inevitable, and a divine right of the United States.

- Manifest destiny was used by Democrats in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico.

- While many writers focus primarily on U.S. expansionism when discussing manifest destiny, others see a broader expression of belief in the country's "mission" in the world.

Key Terms

- expansionism: A nation's policy of broadening its territory or economic influence.

- manifest destiny: The political doctrine or belief held by the United States, particularly during its expansion, that the nation had a special role and divine right to expand westward and gain control over the continent.

- exceptionalism: In the United States, the belief that the nation does not conform to an established norm, and instead has a special and divine role to play.

American Expansionism

Manifest destiny was the 19th century U.S. belief that the country (and more specifically, the white Anglo-Saxon race within it) was destined to expand across the continent. Democrats used the term in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico. The concept was largely denounced by Whigs and fell into disuse after the mid-19th century. Advocates of manifest destiny believed that expansion was not only wise, but that it was readily apparent (manifest) and could not be prevented (destiny).

The concept of U.S. expansionism is in fact much older. It is rooted in European nations' early colonization of the Americas, the establishment of the United States by white Anglo-Saxons from England, and the continued wars against and forced removal of the American Indians indigenous to the lands. In 1845, John L. O'Sullivan, a New York newspaper editor, introduced the concept of "manifest destiny" in the July/August issue of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, in an article titled, "Annexation." The term described the very popular idea of the special role of the United States in overtaking the continent—the divine right and duty of white Americans to seize and settle the continent's western territory, thus spreading Protestant, democratic values.

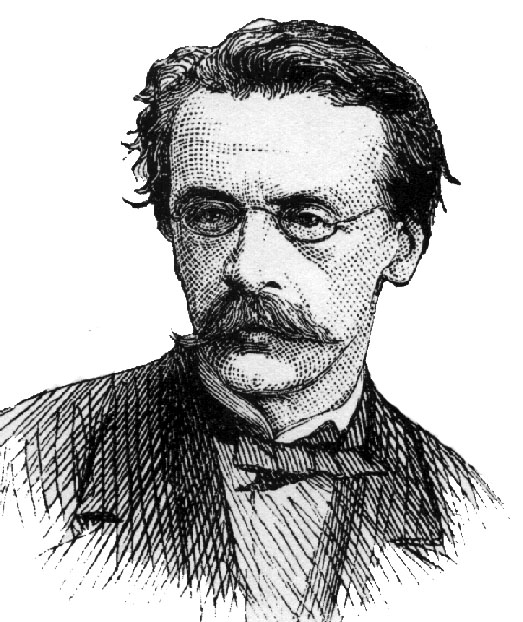

Sketch of John L. O'Sullivan, 1874: John L. O'Sullivan was an influential columnist as a young man, but is now generally remembered only for his use of the phrase "manifest destiny" to advocate the annexation of Texas and Oregon.

Manifest Destiny and Politics

In this climate of opinion, voters in 1844 elected into the presidency James K. Polk, a slaveholder from Tennessee, because he vowed to annex Texas as a new slave state, and to take Oregon. "Manifest destiny" was a term Democrats primarily used to support the Polk Administration's expansion plans. The idea of expansion was also supported by Whigs like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln, who wanted to expand the nation's economy. John C. Calhoun was a notable Democrat who generally opposed his party on the issue, which fell out of favor by 1860.

Manifest destiny was a general notion rather than a specific policy. The term combined a belief in expansionism with other popular ideas of the era, including US exceptionalism and Romantic nationalism. While many writers have focused on US expansionism when discussing manifest destiny, others see in the term a broader expression of a belief in the United States' "mission" in the world, which has meant different things to different people over the years. For example, the belief in an U.S. mission to promote and defend democracy throughout the world, as expounded by Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson, continues to influence US political ideology to this day.

The angel Columbia was an image commonly used at the time to personify the United States. Originating from the name of Christopher Columbus, it was originally used for the 13 colonies and remained the dominant image for the female personification of the United States until the Statue of Liberty displaced it in the 1920s. During the era of manifest destiny, many images were produced of Columbia spreading democracy and other United States values across the western lands.

The Angel Columbia: This 1872 painting depicts Columbia as the "Spirit of the Frontier," carrying telegraph lines across the western frontier to fulfill manifest destiny.

Oregon and the Overland Trails

The Oregon and Overland Trails were two principal routes that moved people and commerce from the east to the west in the 19th century.

Learning Objectives

Examine how establishment of the Oregon and Overland Trails enabled diverse groups to travel west

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Oregon Trail covered approximately 2,000 miles from Missouri, Iowa, or Nebraska, ending in the Oregon Territory.

- The Oregon Trail's initial route was scouted by fur traders and trappers. Each year, as more settlers brought wagon trains along the trail, new cutoff routes were discovered that made the route shorter and safer.

- The Overland Stage Company used the Overland Trail to run mail and passengers to Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Both the Oregon and Overland Trail became obsolete when the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad made traveling west safer, easier, and cheaper.

- The original wave of western settler-invaders along the Oregon and Overland Trails consisted of moderately prosperous, white, US-born farming families from the east.

- More recent immigrants also migrated west, with the largest numbers coming from Northern Europe and Canada. Several thousand African Americans also migrated west following the Civil War.

Key Terms

- Oregon Trail: A 2,000-mile (3,200 km), historic east-west wagon route that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon and locations in between.

- Overland Trail: A stagecoach and wagon trail in the American west during the 19th century.

- Transcontinental Railroad: A continuous train line in the United States that traveled across the country and connected the Pacific coast to the Atlantic coast.

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a 2,000-mile, historic east-west wagon route and emigrant trail that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon and locations in between. The eastern part of the trail spanned part of the future state of Kansas and nearly all of what are now the states of Nebraska and Wyoming. The western half of the trail spanned most of then future states of Idaho and Oregon.

Oregon Trail: The path of the Oregon Trail, spanning the present-day states of Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon.

The beginnings of the Oregon Trail were laid by fur trappers and traders from about 1811 to 1840; these early trails were only passable on foot or by horseback. By 1836, when the first migrant wagon train was organized in Independence, Missouri, a wagon trail had been cleared to Fort Hall, Idaho. Wagon trails were cleared increasingly further west, eventually reaching the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Each year, as more settlers brought wagon trains along the trail, new cutoff routes were discovered that made the route shorter and safer. Improved roads, ferries, and bridges also improved the trip. There were various offshoots in Missouri, Iowa, and the Nebraska Territory; the routes converged along the lower Platte River Valley near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory and led to rich farmlands west of the Rocky Mountains.

From the early to mid-1830s, and particularly through the epochal years of 1846–1869, about 400,000 settlers, ranchers, farmers, miners, and businessmen and their families used the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the California Trail (from 1843), Bozeman Trail (from 1863), and Mormon Trail (from 1847), who used many of the same trails before turning off to their separate destinations. Use of the trail declined as the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, making the trip west substantially faster, cheaper, and safer. Today, modern highways such as Interstate 80 follow the same course westward and pass through towns originally established to service the Oregon Trail.

Overland Trail

The Overland Trail (also known as the Overland Stage Line) was a stagecoach and wagon trail in the American west during the 19th century. While explorers and trappers had used portions of the route since the 1820s, the Overland Trail was most heavily used in the 1860s as an alternative route to the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails through central Wyoming. The Overland Stage Company owned by Ben Holladay famously used the Overland Trail to run mail and passengers to Salt Lake City, Utah, via stagecoaches in the early 1860s. Starting from Atchison, Kansas, the trail descended into Colorado before looping back up to southern Wyoming and rejoining the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger. The stage line operated until 1869, when completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad eliminated the need for mail service via stagecoach.

Ruts on the Oregon Trail: So many wagons traveled the Oregon Trail that ruts are still visible along some sections. This photograph was taken in 2008 in Wyoming.

Who Were the Settlers?

In the 19th century, as today, relocating and starting a new life took money. Because of the initial cost of relocation, land, and supplies, as well as months of preparing the soil, planting, and subsequent harvesting before any produce was ready for market, the original wave of western settler-invaders along the Oregon Trail in the 1840s and 1850s consisted of moderately prosperous, white, native-born farming families from the east. More recent immigrants also migrated west, with the largest numbers coming from Northern Europe and Canada. Germans, Scandinavians, and Irish were among the most common. Compared with European immigrants, those from China were much less numerous, yet still significant.

In addition to a significant European migration westward, several thousand African Americans migrated west following the Civil War, as much to escape the racism and violence of the Old South as to find new economic opportunities. The latter were were known as exodusters, referencing the biblical flight from Egypt, because they fled the racism of the South, with most headed to Kansas from Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. By 1890, over 500,000 African Americans lived west of the Mississippi River.

The Western Frontier

As the nation expanded westward, settlers were motivated by opportunities to farm the land or "make it rich" through cattle or gold.

Learning Objectives

Describe the conditions common in western frontier towns

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- While the motivation for private profit dominated much of the movement westward, the federal government played a supporting role in securing land and maintaining law and order.

- The rigors of life in the West presented many challenges to homesteaders, such as dry and barren land, droughts, insect swarms, shortages of materials, and lost crops.

- Although homestead farming was the primary goal of most western settlers in the latter half of the 19th century, a small minority sought to make fortunes quickly through other means, such as gold or cattle.

- The American West became notorious for its hard mining towns, such as Deadwood, South Dakota and Tombstone, Arizona, and entrepreneurs in these and other towns set up stores and businesses to cater to the miners.

Key Terms

- Homesteading: A lifestyle of self-sufficiency characterized by subsistence agriculture and home preservation of foodstuffs; it may or may not also involve the small-scale production of textiles, clothing, and craftwork for household use or sale.

Moving West

The Federal Role

While the motivation for private profit dominated much of the movement westward, the federal government played a supporting role in securing land and maintaining law and order. Despite the Jeffersonian aversion to, and mistrust of, federal power, the government bore more heavily into the West than any other region, fueled by the ideas of manifest destiny. Because local governments in western frontier towns were often nonexistent or weak, westerners depended on the federal government to protect them and their rights.

The federal government established a sequence of actions related to control over western lands. First, it sent surveyors and explorers to map and document the land and ultimately acquire western territory from other nations or American Indian tribes by treaty or force. Next, it ordered federal troops to clear out and subdue any resistance from American Indians. It subsidized the construction of railroad lines to facilitate westward migration, and finally, it established bureaucracies to manage the land (such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Land Office, US Geological Survey, and Forest Service). By the end of the 19th century, the federal government had amassed great size, power, and influence in national affairs.

Transportation

Transportation was a key issue in westward expansion. The Army (especially the Army Corps of Engineers) was given full responsibility for facilitating navigation on the rivers. The steamboat, first used on the Ohio River in 1811, made inexpensive travel using the river systems possible. The Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and their tributaries were especially used for this purpose. Army expeditions up the Missouri River from 1818 to 1825 allowed engineers to improve the technology. For example, the Army's steamboat, the Western Engineer, of 1819 combined a very shallow draft with one of the earliest stern wheels. During this period, Colonel Henry Atkinson developed keelboats with hand-powered paddle wheels.

In addition to river travel, the Oregon and Overland Trails allowed for increased travel and migration to the West. The completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 dramatically changed the pace of travel in the country, as people were able to complete in a week a route that had previously taken months.

Life in the West

Homesteading

The rigors of life in the West presented many challenges and difficulties to homesteaders. The land was dry and barren, and homesteaders lost crops to hail, droughts, insect swarms, and other challenges. There were few materials with which to build, and early homes were made of mud, which did not stand up to the elements. Money was a constant concern, as the cost of railroad freight was exorbitant, and banks were unforgiving of bad harvests. For women, life was especially difficult; farm wives worked at least 11 hours a day on chores and had limited access to doctors or midwives. Still, many women were more independent than their eastern counterparts and worked in partnership with their husbands.

As the railroad expanded and better farm equipment became available, by the 1870s, large farms began to succeed through economies of scale. Yet small farms still struggled to stay afloat, leading to rising discontent among the farmers, who worked so hard for so little success.

Western Frontier Towns

Although homestead farming was the primary goal of most western settlers in the latter half of the 19th century, a small minority sought to make their fortunes quickly through other means. Specifically, gold (and subsequently silver and copper) prospecting attracted thousands of miners looking to get rich quickly before returning East. In addition, ranchers capitalized on newly available railroad lines to move longhorn steers that populated southern and western Texas. This meat was highly sought after in eastern markets, and the demand created not only wealthy ranchers but an era of cowboys and cattle drives that in many ways defines how we think of the West today. Although neither miners nor ranchers intended to remain permanently in the West, many individuals from both groups ultimately stayed and settled there.

The American West became notorious for its hard mining towns. Deadwood, South Dakota, in the Black Hills, was an archetypal late gold town founded in 1875. Although the town was far from any railroad, 20,000 people lived there as of 1876. Tombstone, Arizona was a notorious mining town that flourished longer than most, from 1877 to 1929. Silver was discovered there in 1877, and by 1881 the town had a population of over 10,000. Entrepreneurs in these and other towns set up stores and businesses to cater to the miners. Gambling and prostitution were central to life in these western towns, and only later―as the female population increased and reformers moved in―did prostitution become somewhat less common.

The popular image of the Wild West portrayed in books, television, and film has been one of violence and mayhem. The lure of quick riches through mining or driving cattle meant that much of the West indeed consisted of rough men living a rough life, although the violence was exaggerated and even glorified in the dime-store novels of the day. The exploits of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, and others made for good stories, but the reality was that western violence was more isolated than the stories might suggest. These clashes often occurred as people struggled for the scarce resources that could make or break their chance at riches, or as they dealt with the sudden wealth or poverty that prospecting provided.

As wealthy men brought their families west, the lawless landscape slowly began to change. Abilene, Kansas is one example of a lawless town, replete with prostitutes, gambling, and other vices, that transformed when middle-class women arrived in the 1880s with their husbands. These women began to organize churches, schools, civic clubs, and other community programs to promote family values.

Western mining towns: The first gold prospectors in the 1850s and 1860s worked with easily portable tools that allowed them to follow their dream and try to strike it rich (a). It did not take long for the most accessible minerals to be stripped, making way for large mining operations, including hydraulic mining, where high-pressure water jets removed sediment and rocks (b).

Women in the West

Women were vitally important in the settlement of the West.

Learning Objectives

Describe the experience of women in the western frontier

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Women held many responsibilities during the westward expansion, such as managing the movement of households overland, establishing social activities in pioneer settlements, and sharing the hard labor of farming new land.

- Frontier life was highly social, and women participated in many activities with their neighbors such as barn raising, corn husking, and quilting bees.

- Some women found work in the sex trade in early mining towns.

- Eventually, frontier towns attracted women who worked as laundresses and seamstresses, and organized church societies and other reform movements.

- The western frontier also gave rise to many famous women who countered traditional gender roles, such as Annie Oakley, Pearl Hart, and Nellie Cashman.

Key Terms

- barn raisings: A collective action of a community in which a building is assembled collectively by members of the community.

- prostitution: Engaging in sexual activity with another person in exchange for compensation, such as money or other valuable goods.

- Grange: A farmers' association organized in 1867. Officially called The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry. The association operates at the local, county, and state levels by sponsoring social activities, community service, and political lobbying and promoting economic and agricultural unity in communities.

- brothel: A house of prostitution.

Farm Life

During the early years of settlement on the Great Plains, women played an integral role in ensuring family survival by working the fields alongside their husbands and children. This was in addition to their handling of many other responsibilities, such as child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family and hired hands, and managing the housework. As late as 1900, a typical farm wife could expect to devote 9 hours per day to chores such as cleaning, sewing, laundering, and preparing food. Two additional hours were spent cleaning the barn and chicken coop, milking the cows, caring for the chickens, and tending the family garden.

While some women could find employment in the newly settled towns as teachers, cooks, or seamstresses, they originally were deprived of many rights. Women were not permitted to sell property, sue for divorce, serve on juries, or vote. For the vast majority of women, work was not in towns for money, but on the farm. Despite these obstacles, the challenges of farm life eventually empowered women to break through certain legal and social barriers. Many lived more equitably as partners with their husbands than did their eastern US counterparts. If widowed, a wife typically took over responsibility for the farm, a level of management very rare back east, where the farm would fall to a son or another male relation. Pioneer women made important decisions and were considered by their husbands to be more equal partners in the success of the homestead. This was because of the necessity that all members had to work hard and contribute to the farming enterprise for it to succeed. Therefore, it is not surprising that the first states to grant women's rights, including the right to vote, were those in the Pacific Northwest and Upper Midwest, where women pioneers worked the land side by side with men.

Outside the family, women also played a crucial role in the community. People living in rural areas created rich social lives for themselves, often sponsoring activities that combined work, food, and entertainment, such as barn raising, corn husking, quilting bees, Grange meetings, church activities, and school functions. Women also organized shared meals, potluck events, and extended visits between families.

Homesteading family: Many women traveled west with family groups, such as the mother in this 1886 photograph.

Ranching and Mining Towns

While homesteaders were often families, gold speculators and ranchers tended to be single men in pursuit of fortune. The few women who went to these wild outposts were typically prostitutes, and even their numbers were limited. In 1860, in the Comstock Lode region of Nevada, for example, there were reportedly only 30 women in a town with some 2,500 men.

Women found occupations in all walks of frontier life. Some women worked in brothels despite the harsh and dangerous working conditions. Many Chinese women, for example, came to the western camps as prostitutes to make money to send back home. Some of the "painted ladies" who began as prostitutes eventually owned brothels and became businesswomen in their own right. However, life for these young women remained a challenging one as western settlement progressed. A handful of women, no more than 600, braved both the elements and male-dominated culture to become teachers in several of the more established cities in the West. Even fewer arrived to support their husbands or operate stores in the mining towns.

Toward the latter part of the 19th century, wealthy men began bringing their families west, and the mostly lawless landscape slowly began to change. Middle-class women arrived in the 1880s with their husbands and established boarding houses, organized church societies, and worked as laundresses and seamstresses. These women began to organize churches, school, civic clubs, and other community programs to promote family values. They fought to remove opportunities for prostitution and other vices they felt threatened their values. Protestant missionaries eventually joined the women in their efforts, and Congress responded by passing both the Comstock Law (named after its chief proponent, anti-obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock) in 1873 to ban the spread of "lewd and lascivious literature" through the mail, and the subsequent Page Act of 1875 to prohibit transportation of women into the United States for employment as prostitutes. However, the brothels continued to operate and remained popular throughout the West despite reformers' efforts.

Famous Women of the West

The western frontier also gave rise to many famous women, including Annie Oakley, Pearl Hart, and Nellie Cashman.

Annie Oakley

Annie Oakley (1860–1926) was an American sharpshooter and exhibition shooter whose talent first came to light when, at age 15, she won a shooting match with traveling show marksman Frank E. Butler (whom she later married). The couple joined Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, and later Oakley became a renowned international star, performing before royalty and heads of state.

Pearl Hart

Pearl Hart (c. 1871 to after 1928) was a Canadian-born outlaw of the American Old West. She committed one of the last recorded stagecoach robberies in the United States. Her crime gained notoriety primarily because she was a woman. Many details of Hart's life are uncertain, with available reports often varied and contradictory.

Nellie Cashman

Ellen "Nellie" Cashman (1845–1925) became known across the American West and in western Canada as a nurse, restaurateur, businesswoman, Roman Catholic philanthropist in Arizona, and gold prospector in Alaska. A native of County Cork, Ireland, she and her sister were brought as young children to the United States by their mother around 1850 to escape the poverty of the Great Famine. Cashman established her first boarding house for miners in British Columbia during the Klondike Gold Rush. During her time there, she led a rescue of dozens of miners in the Cassiar Mountains.

After moving to Tombstone, Arizona, around 1880, Cashman built the Sacred Heart Catholic Church and did charitable work with the Sisters of St. Joseph. In the late 1880s, Cashman set up several restaurants and boarding houses in Arizona. In 1898, she went to the Yukon for gold prospecting, and worked there until 1905. She became nationally known as a frontierswoman, with the Associated Press covering a later trip.

Annexing Texas

After a series of skirmishes with Mexico, the Republic of Texas won independence in 1836 and was annexed into the United States in 1845.

Learning Objectives

Examine the economic motivations behind the Mexico and Texas war and the subsequent annexation of Texas by the United States

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Following Mexico's gaining independence from Spain in 1821, American settlers immigrated to Texas in large numbers, intent on taking the land from the new and vulnerable Mexican nation to create a new US slave state.

- Anglo-American settlers in Texas were not pleased with Mexico's religious practices, legal system, and 1829 abolition of slavery.

- In March 1836, the Consultation in Texas declared independence from Mexico and drafted a constitution calling for a US-style judicial system and an elected president and legislature.

- The Battle of the Alamo was a pivotal point in the Texas Revolution; the Republic of Texas won independence from Mexico in 1836.

- The first overtures to annex the new Republic of Texas to the United States began in 1837, but the United States declined, believing it would lead to war with Mexico.

- Texas's annexation to the United States was ultimately accomplished in 1845 during the final days of the Tyler administration.

Key Terms

- Republic of Texas: An independent sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836 to February 19, 1846.

- Sam Houston: A 19th-century American statesman, politician, and soldier, best known for his leading role in bringing Texas into the United States.

- annexation: The permanent acquisition and incorporation of a territorial entity into another geopolitical entity (either adjacent or non-contiguous).

US Migration into Texas

American expansionists had long coveted the area of Spain's empire known as Texas. After the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty established the boundary between Mexico and the United States, more American expansionists began to move into the northern portion of the Mexican province of Coahuila y Tejas. Following Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821, US settlers immigrated to Texas in even larger numbers, intent on taking the land from the new and vulnerable Mexican nation in order to create a new US slave state.

Anglo-Americans, primarily from the southern United States, began emigrating to Mexican Texas in the 1820s at the request of the Mexican government, which sought to populate the sparsely inhabited lands of its northern frontier and mitigate attacks from American Indian tribes in the region. Anglo-Americans soon became a majority in Texas and quickly became dissatisfied with Mexican rule. The soil and climate were conducive to expanding slavery and the cotton kingdom. To many whites, it seemed not only their God-given right but also their patriotic duty to populate the lands beyond the Mississippi River, bringing with them American slavery, culture, laws, and political traditions.

Rising Tensions

Anglo-American settlers in Texas, who were primarily Protestant, were discontented with Mexico's prohibition of public practice of religions other than Catholicism. They were also dissatisfied with the Mexican legal system, which was markedly different from the representative democracy and jury trials found in the United States. Of greatest concern, however, was the Mexican government's 1829 abolition of slavery. Most US settlers were from southern states, and many had brought slaves with them. Mexico tried to accommodate them by maintaining the questionable assertion that the slaves were indentured servants. However, American slaveholders in Texas distrusted the Mexican government and wanted Texas to be a new US slave state. The great dislike for Roman Catholicism coupled with a widely held belief in American racial superiority led to a generally racist and discriminatory view toward Mexicans.

Declaring Independence

Fifty-five delegates from the Anglo-American settlements in Texas gathered in 1831 with demands including creation of an independent state of Texas separate from Coahuila. When ordered to disband, the delegates reconvened in early April 1833 to write a constitution for an independent Texas. While Mexican President General Antonio López de Santa Anna, agreed to many of their demands, he did not grant statehood. The Consultation delegates met again in March of 1836. They declared their independence from Mexico and drafted a constitution calling for a US-style judicial system and an elected president and legislature. Notably, they also established that slavery would not be prohibited in Texas. Many wealthy Tejanos supported the push for independence, hoping for liberal governmental reforms and economic benefits.

Battle of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution

Mexico had no intention of losing its northern province. Santa Anna and his army of some 4,000 troops had besieged San Antonio in February 1836. Hopelessly outnumbered, its 200 defenders fought fiercely from their refuge in an old mission known as the Alamo.

The Battle of the Alamo, as it came to be called, lasted from February 23 to March 6, 1836. This was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under Santa Anna launched an assault on the Alamo Mission, and all of the Texian defenders were killed. Santa Anna's perceived cruelty during the battle inspired many Texians—both Texas settlers and adventurers from the United States—to join the Texian Army. Buoyed by a desire for revenge, the Texians defeated the Mexican army at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, ending the revolution. Sam Houston became the first president of the Republic of Texas, elected on a platform that favored annexation to the United States.

Battle of the Alamo: The Fall of the Alamo, painted by Theodore Gentilz fewer than 10 years after this pivotal moment in the Texas Revolution, depicts the 1836 assault on the Alamo complex.

Lone Star Republic and the Issue of Annexation

Mindful of the vicious debates over Missouri that had led to talk of disunion and war, US politicians were reluctant to annex Texas or, indeed, even to recognize it as a sovereign nation. Annexation would almost certainly trigger war with Mexico, and admission of a state with a large slave population, though permissible under the Missouri Compromise, would once again bring the issue of slavery to the fore. Texas had no choice but to organize itself as the independent Lone Star Republic. To protect itself from Mexican attempts to reclaim it, Texas sought and received recognition from France, Great Britain, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The United States did not officially recognize Texas as an independent nation until March 1837, nearly a year after the final victory over the Mexican army at San Jacinto.

Uncertainty about its future, however, did not discourage Americans committed to expansion, especially slaveholders, from rushing to settle in the Lone Star Republic. Between 1836 and 1846, its population nearly tripled. By 1840, American slaveholders had brought nearly 12,000 enslaved Africans to Texas. In keeping with the program of ethnic cleansing and white racial domination, Americans in Texas generally treated both Mexican Tejano and American Indian residents with contempt, eager to displace and dispossess them.

In August 1837, Memucan Hunt, Jr., the Texan minister to the United States, submitted an annexation proposal to the Van Buren administration. Believing that annexation would lead to war with Mexico, the administration declined Hunt's proposal. After the election of Mirabeau B. Lamar, an opponent of annexation, as president of Texas in 1838, Texas withdrew its offer. Texas would not become annexed to the United States until 1845 in the final days of President Tyler's administration.

Tyler and Texas

John Tyler's presidency was marked by a series of moves favoring American expansionism, including the annexation of Texas.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate John Tyler's presidency and his political agenda that led to American expansion

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- President John Tyler frequently used the language of manifest destiny to promote expansionist policies.

- Tyler applied the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii, forbidding Britain from exerting influence there, and paved the way for the annexation of Hawaii as a state many years later.

- While Tyler knew that re-election was unlikely, he worked to convert his political defeat into a success for the annexation of Texas, thereby securing his political legacy.

- On February 26, 1845, 6 days before Polk took office, Congress passed the joint resolution for the annexation of Texas, and Tyler signed the bill into law 3 days before the end of his term.

- There was an ongoing border dispute between the Republic of Texas and Mexico prior to annexation; Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its border while Mexico maintained that it was the Nueces River.

Key Terms

- James K. Polk: The 11th President of the United States (1845–1849).

- John Tyler: The 10th President of the United States (1841–1845), after being the 10th Vice President of the United States (1841).

- manifest destiny: The political doctrine or belief held by the United States, particularly during its expansion, that the nation had a God-given right to expand toward the West.

President John Tyler

While John Tyler had a difficult time with domestic policy during his presidency (1841–1845), he oversaw many accomplishments in foreign policy, especially in the areas of westward expansion. He had long been an advocate of expansion toward the Pacific, and of free trade, and was fond of evoking themes of national destiny and the spread of liberty in support of these policies. His presidency continued Andrew Jackson 's earlier efforts to promote US commerce across the Pacific. He applied the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii, told Britain not to interfere there, and began the process toward eventual US annexation of Hawaii. In 1842, Secretary of State Daniel Webster negotiated the Webster–Ashburton Treaty with Britain, which concluded where the border between Maine and Canada lay. However, Tyler was unsuccessful in concluding a treaty with the British to fix Oregon's boundaries. On Tyler's last full day in office, March 3, 1845, Florida was admitted to the Union as the 27th state.

Americans at this time asserted a right to colonize vast expanses of North America beyond their country's borders, especially in Oregon, California, and Texas. By the mid-1840s, US expansionism was articulated in the ideology of manifest destiny. Major events in the western movement of the US population were the Homestead Act, a law by which, for a nominal price, a settler was given a title to 160 acres of land to farm. Other significant events included the opening of the Oregon Trail, the Mormon Emigration to Utah in 1846–'47, the California Gold Rush of 1849, the Colorado Gold Rush of 1859, and the completion of the nation's First Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869.

The Issue of Texas

Following the slaveholder Tyler's break with the Whigs in 1841, he had begun to shift back to his old Democratic party. However, its members were not ready to receive him. He knew that with little chance of re-election, the only way to salvage his presidency and legacy was to move public opinion in favor of the Texas issue, and he formed his own political party to lobby the Democratic Party in favor of annexation.

Tyler supporters with signs reading "Tyler and Texas!" held their nominating convention in Baltimore in May 1844, just as the Democratic Party was also nominating its presidential candidate. With their high visibility and energy, they were able to force the Democrats' hand in favor of annexation. Ballot after ballot, Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren failed to win the necessary super- majority of Democratic votes and slowly fell in the ranking. It was not until the ninth ballot that the Democrats discovered an obscure pro-annexation candidate named James K. Polk. They found him to be perfectly suited for their platform, and he was nominated with two-thirds of the vote. Tyler considered his work vindicated and implied in an acceptance letter that annexation was his true priority, rather than re-election.

President Tyler entered negotiations with the Republic of Texas for an annexation treaty, which he submitted to the Senate. On June 8, 1844, the treaty was defeated 35 to 16, well below the two-thirds majority necessary for ratification. Of the 29 Whig senators, 28 voted against the treaty with only one Whig, a southerner, supporting it. The Democratic senators were more divided on the issue; in the north, six opposed while five supported the treaty, while one opposed and 10 supported it in the south.

Election of 1844

Tyler was unfazed, however, and he felt annexation was now within reach. He called for Congress to annex Texas by joint resolution rather than by treaty. Former President Jackson, a staunch supporter of annexation, persuaded presidential candidate Polk to welcome Tyler back into the Democratic party, and ordered Democratic editors to cease their attacks on the him. Satisfied by these developments, Tyler dropped out of the presidential race in August and endorsed Polk for the presidency. Polk's narrow victory over Clay in the November election was seen by the Tyler administration as a mandate for completing the resolution.

Annexation

After the election, the Tyler administration consulted with President-elect Polk and set out to accomplish annexation via a joint resolution. The resolution declared that Texas would be admitted as a state as long as it approved annexation by January 1, 1846, that it could split itself into four additional states, and that possession of the Republic's public land would shift to the state of Texas upon its admission. On February 26, 1845, 6 days before Polk took office, Congress passed the joint resolution, and Tyler signed the bill into law on March 1, just 3 days before the end of his term.

On July 4, 1845, the Texan Congress endorsed the American annexation offer with only one dissenting vote, and began writing a state constitution. The citizens of Texas approved the new constitution and the annexation ordinance on October 13, 1845, and President Polk signed the documents formally integrating Texas into the United States on December 29, 1845.

Texas and Mexico Border

Prior to annexation there was an ongoing border dispute between the Republic of Texas and Mexico. Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its border, while Mexico maintained it was the Nueces River, and did not recognize Texan independence. President Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to garrison the southern border of Texas, as defined by the former Republic. Taylor moved into Texas, ignoring Mexican demands to withdraw. Indeed, Taylor marched as far south as the Rio Grande, where he began to build a fort near the river's mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. The Mexican government regarded this action as a violation of its sovereignty.

The Republic of Texas never controlled what is now New Mexico, and the failed Texas Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 was its only attempt to take that territory. El Paso was only taken under Texas governance by Robert Neighbors in 1850, over 4 years after annexation. Neighbors was not welcomed in New Mexico. Texas continued to claim New Mexico as far as the Rio Grande, supported by the rest of the South and opposed by the North and by New Mexico itself. The Texas/New Mexico boundary was not established until the Compromise of 1850.

John Tyler, c. 1841: John Tyler endorsed the idea of manifest destiny to defend the continued expansion of the United States, including the annexation of Texas.

Polk and Expansion

President James K. Polk was a strong proponent of expansionism and achieved the acquisition of Texas, Oregon, and California during his administration.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the strategies President Polk used to achieve American expansion

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- James K. Polk called the annexation of Oregon, Texas, and California main goals of his one-term presidency.

- Polk's envoy negotiated the purchase of Oregon from Britain in 1846 at the 49th parallel and not the 54th parallel, as many had wanted.

- After the 1845 annexation of Texas, border disputes between the United States and Mexico led to the Mexican–American War.

- The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican–American War in 1848 and led to the addition of California to the United States.

Key Terms

- Oregon Territory: An organized incorporated area of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848 to February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union.

- Mexican–American War: An armed conflict between the United States and Mexico spanning 1846–1848 in the wake of the 1845 US annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory despite the 1836 Texas Revolution.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: The document that ended the Mexican–American War on February 2, 1848.

President James K. Polk

James K. Polk, at age 49 the youngest president at that time to be inaugurated, set out a series of goals, two of which were explicitly related to US expansion. He intended to acquire some or all of Oregon Country from Britain, as well as California and New Mexico from Mexico. He pledged to accomplish all of these objectives in a single term. By linking acquisition of new lands in Oregon (with no slavery ) and Texas (with slavery), he hoped to satisfy both the North and the South.

Polk strongly supported expansion. Democrats believed that opening up more land for yeoman farmers was critical for the success of republican virtue. Like most Southerners, he supported the annexation of Texas. To balance the interests of the North and the South, he also wanted to acquire the Oregon Country (present-day Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and British Columbia ), and he sought to purchase California from Mexico.

James K. Polk: Daguerreotype of President Polk taken by Mathew Brady on February 14, 1849, near the end of his presidency.

During his presidency, many abolitionists harshly criticized Polk as an instrument of "Slave Power" and claimed that he supported the annexation of Texas, as well as the later war with Mexico, for the purpose of spreading slavery. Polk believed slavery could not exist in the territories won from Mexico but refused to endorse the Wilmot Proviso that would forbid it there.

U.S. Expansion under President Polk

Oregon

Polk heavily pressured Britain to resolve the Oregon boundary dispute. Since 1818, the territory had been under the joint occupation and control of the United Kingdom and the United States. Previous US administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel, which was not acceptable to Britain, as they had commercial interests along the Columbia River. Polk was at first willing to compromise, but when the British again refused to accept the 49th parallel boundary proposal he broke off negotiations and returned to the Democratic "All Oregon" demand (which called for all of Oregon up to the 54–40 line that marked the southern boundary of Russian Alaska). The rallying cry "54–40 or fight!" became popular among Democrats.

Polk wanted territory, not war, so he compromised with the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Aberdeen. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 divided the Oregon Country along the 49th parallel, as in the original US proposal. Although there were many who still clamored for the entire territory, the Senate approved the treaty. By settling for the 49th parallel, Polk angered many midwestern Democrats. Many of these Democrats believed that Polk had always wanted the boundary at the 49th, and that he had fooled them into believing he wanted it at the 54th. The portion of Oregon territory the United States acquired later formed the states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming.

Texas

Upon hearing of Polk's election to office in 1844, President John Tyler urged Congress to pass a joint resolution admitting Texas to the Union. Congress complied on February 28, 1845. Texas promptly accepted the offer and officially became a state on December 29, 1845. The annexation angered Mexico, which had lost Texas in 1836, and Mexican politicians had repeatedly warned that annexation would lead to war. Nevertheless, just days after the resolution passed Congress, Polk declared in his inaugural address that only Texas and the United States would decide whether to annex.

California

After the Texas annexation, Polk turned his attention to California, hoping to acquire the territory from Mexico before any European nation could do so. The main interest was San Francisco Bay, as an access point for trade with Asia. In 1845, he sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico to purchase California and New Mexico for $24–30 million. Slidell's arrival caused political turmoil in Mexico after word leaked that he was there to purchase additional territory and not to offer compensation for the loss of Texas. The Mexicans refused to receive him, citing a technical problem with his credentials.

In January 1846, to increase pressure on Mexico to negotiate, Polk sent troops under General Zachary Taylor into the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande—territory that was claimed by both the United States and Mexico. This action soon led to the Mexican–American War, which the United States won. As part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, Polk achieved his goal of adding California to the United States.

Proclamation of War Against Mexico: Polk's presidential proclamation of war against Mexico.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: The Mexican Cession (in red) was acquired through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War. The Gadsden Purchase (in orange) was acquired through purchase after Polk left office.

The war had serious consequences for Polk and the Democrats, however. It gave the Whig Party a unifying message of denouncing the war as an immoral act of aggression carried out through abuse of presidential power. In the 1848 election, however, the Whigs nominated General Zachary Taylor, a war hero, and celebrated his victories. Taylor refused to criticize Polk. As a result of the strain of managing the war effort directly and in close detail, Polk's health markedly declined toward the end of his presidency.

Who Made Up The Grange, And What Effect Did They Have On The Writing Of The Texas Constitution?

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/manifest-destiny/

Posted by: martineztiff1979.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Who Made Up The Grange, And What Effect Did They Have On The Writing Of The Texas Constitution?"

Post a Comment